Last week I talked about how I was doing some collaborative worldbuilding with my new group. I spoke about how involving your players in the worldbuilding process is a rich and rewarding experience and how I had come up with a method to do it that was working great. Well, here it is. I’m calling it the Dragon’s Kingdom. It’s based on the entanglements system for building a game. You need a poster map and a marker. It consists of 3 steps:

Step 1 – Dictates

For the first step your players (and you, if you choose) each write an overarching rule for your setting. They can be anything like ‘magic is dangerous and feared’, ‘dragons are extinct’ or ‘the spirits have abandoned the world, primal power does not exist’. The idea is to not make them to specific. Aim for between 8-12. Make sure your group knows these aren’t set in stone. More on that later.

Step 2 – World

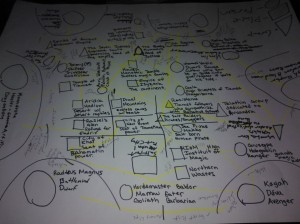

For this step, the players (and you if you choose) will place people, places, and groups on the map. People are represented by circles. Places are squares. Groups are triangles. Each item placed should be named. The first part is everyone puts a circle in front of themselves for their character. You can also place one for the antagonist if you so choose. Then, on the first round of step one, each person will place two items on the map. Every round after, each person will place one item. Aim for 4 or 5 rounds, depending on the size of your group.

Step 3 – Relationships

This is the fun step. Your players (and again, you if you choose) will map how the people, places, and things in your setting relate to each other. To do this, those participating draw lines from the items on the map to other items on the map. Then, the relationship between those items is defined by who drew the line. During the first round, each person draws 2 relationships. The next round is what I call a ‘meta-round’. In a meta-round, the person whose turn it is has the choice of drawing a new relationship or altering something. They can draw a line through a relationship and define how that relationship ended or they can alter a dictate by adding to it. Yes, a person can redraw the altered relationship, representing a further change to it. Also, a dictate cannot be removed and it can only be altered once. For example, with the ‘dragons are extinct’ example I changed it by writing ‘assumed, because they haven’t been seen in a long time.’ After this each person draws a relationship. Then you do another meta-round. Go on like this until you feel there are enough relationships on your map.

So there you have it, the Dragon’s Kingdom. You have my full permission to use it. Let me know if it works for you too!